“You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.” This classic line from Inigo Montoya in “The Princess Bride” encapsulates one of our greatest modern struggles: using the same words, but talking about radically different things.

I saw this first hand last week, spending 2 days touring Civil Rights landmarks with 3 friends. We were trying to immerse ourselves in the story of our nation in a way that no book can do justice. We visited museums dedicated to slavery and voting rights, walked across Edmund Pettis Bridge, and sat in the pews of 16th St. Baptist Church – the site of the 1963 bombing that killed 4 young girls. We walked where giants walked and stood where history was made.

It is not a comfortable history. You cannot visit these places without seeing both the heights of courage and conviction and the lows of human cruelty and hatred. Yet at almost every turn, there is the language of faith. On one hand, the Civil Rights movement flowed through the Church, in both its buildings and it’s leaders. So many of its most prominent voices were pastors and believers who, in the words of John Lewis, “prayed with their feet.” The justice they sought was rooted in the Gospel that Jesus preached – good news to the poor, and liberation for the captives (Is. 61:1-4).”

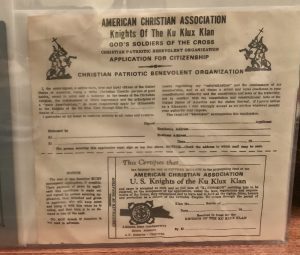

But the language of faith was also prominent in those who opposed them. In the National Voting Rights Museum, a Ku Klux Klan display held an application for membership into their organization, titled the “American Christian Association.” They referred to themselves as “God’s soldier’s for the cross.” Applicants for the White Citizen’s Council (a parallel organization to the KKK) were required to uphold “the tenets of the Christian religion.” They expressed concern for their country and their freedom, the education of their children, and a government becoming “captive of minority group racial politics.” Later, we’d learn that the Klan bombers of  16th St. Baptist Church planned the deadly attack in the basement of their own Methodist Church. Their gospel was good news – but it was only good news for those who looked and voted like them.

16th St. Baptist Church planned the deadly attack in the basement of their own Methodist Church. Their gospel was good news – but it was only good news for those who looked and voted like them.

Both sides claimed Christ. Both sides spoke of freedom. And yet the divergence of their message and mission could not be further apart. They believed and lived from radically different gospels. And now, over a half a century later, they have produced and nurtured two radically different and persistent legacies – legacies that continue to battle for our imagination. And now today, what we mean when we say Christian, what we mean when we say freedom – has never mattered more.

Back in 2017, Beth Moore wisely wrote, “It will become increasingly vital that we learn to distinguish between what is pro-Christian and what is actually Christlike.” So much of what is labeled as “Christian” in our American cultural landscape looks absolutely nothing like Jesus. Defending Christ in un-Christlike ways dishonors the One we claim to follow. When prominent pastors and worship leaders threaten violence towards those who oppose them, when leaders put theological framing around bogus conspiracy theories, when Christians intentionally misrepresent and belittle their political counterparts, and when life-saving medical breakthroughs are opposed in the name of “faith over fear,” we put a Jesus on display that is foreign to the Scriptures. We might be pro-Christian, but we’re no longer Christlike. And that’s a problem.

As I sat in the pews of 16th Street Baptist Church, I thought about the kind of faith I wanted to live. I thought about the Jesus I wanted to follow – the Jesus I wanted people to see. The men and women of this historical Church proclaimed the gospel of Jesus Christ with boldness, held to orthodox Christian doctrine, and taught the Scriptures faithfully – while also seeking freedom for their brothers and sisters through boycotts, non-violent protests, sit-ins, and struggles for voting rights. Their freedom wasn’t just about them. In the words of one of the great voices of their time, Fanny Lou Hamer, “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.”

wanted to follow – the Jesus I wanted people to see. The men and women of this historical Church proclaimed the gospel of Jesus Christ with boldness, held to orthodox Christian doctrine, and taught the Scriptures faithfully – while also seeking freedom for their brothers and sisters through boycotts, non-violent protests, sit-ins, and struggles for voting rights. Their freedom wasn’t just about them. In the words of one of the great voices of their time, Fanny Lou Hamer, “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.”

This is the freedom I see in the Scriptures in the words of Paul: “You, my brothers and sisters, were called to be free. But do not use your freedom to indulge the flesh;rather, serve one another humbly in love. For the entire law is fulfilled in keeping this one command: “Love your neighbor as yourself (Gal. 5:13-14).” American freedom may be about our good, but Christian freedom is about everybody’s good. According to the “royal law of love,” the greatest act of freedom we have as a followers of Jesus is the ability to sacrificially love our neighbors as ourselves.

And by doing so – by being a cruciformed people who see and live beyond our “rights” – we will show ourselves to be more than “Christian.” We’ll be Christlike. And that, my friends, is freedom.